Out With the Baby Talk; Up With the MLU

Feeling daunted by the terms “morphemes” and “MLU”? Let me break these concepts down so you can help your child leave “baby talk” behind!

“Want bunny,” your little one says. “He fuzzy.”

When people say “baby talk,” what do they mean?

They’re not just referring to the immature speech of a little one. They’re also talking about the language –– including words, grammar parts, and sentence structure –– a child uses.

If you return to the sample phrases above, you’ll notice the missing pieces –– and those pieces are making this child’s language sound like “baby talk.”

If the same utterances were expressed in a more mature manner, they would read:

“I want the bunny. He’s fuzzy.”

What do those added languages pieces have in common? They’re all grammatical morphemes.

What Are Morphemes?

In linguistics and child language development, “morpheme” is a word used to describe the smallest unit of language that has meaning.

Lexical vs. Grammatical Morphemes

There are different types of morphemes. Some morphemes express concrete ideas; you can picture what they mean. We call these lexical (or content) morphemes. Here are some examples of lexical morphemes:

“boat”

“sail”

“jacket”

“sun”

“shine”

“float”

Others give grammatical information or tie words together grammatically; they’re less concrete. We call these grammatical (or function) morphemes. Here are some examples of grammatical morphemes:

“a” (an article)

“-s” (denotes plural)

“-ing” (denotes present progressive verb tense)

“-s” (denotes possession)

“a-” (changes verb to adjective)

Breaking Down Words

A morpheme doesn’t necessarily correspond to a syllable or word, although it sometimes does.

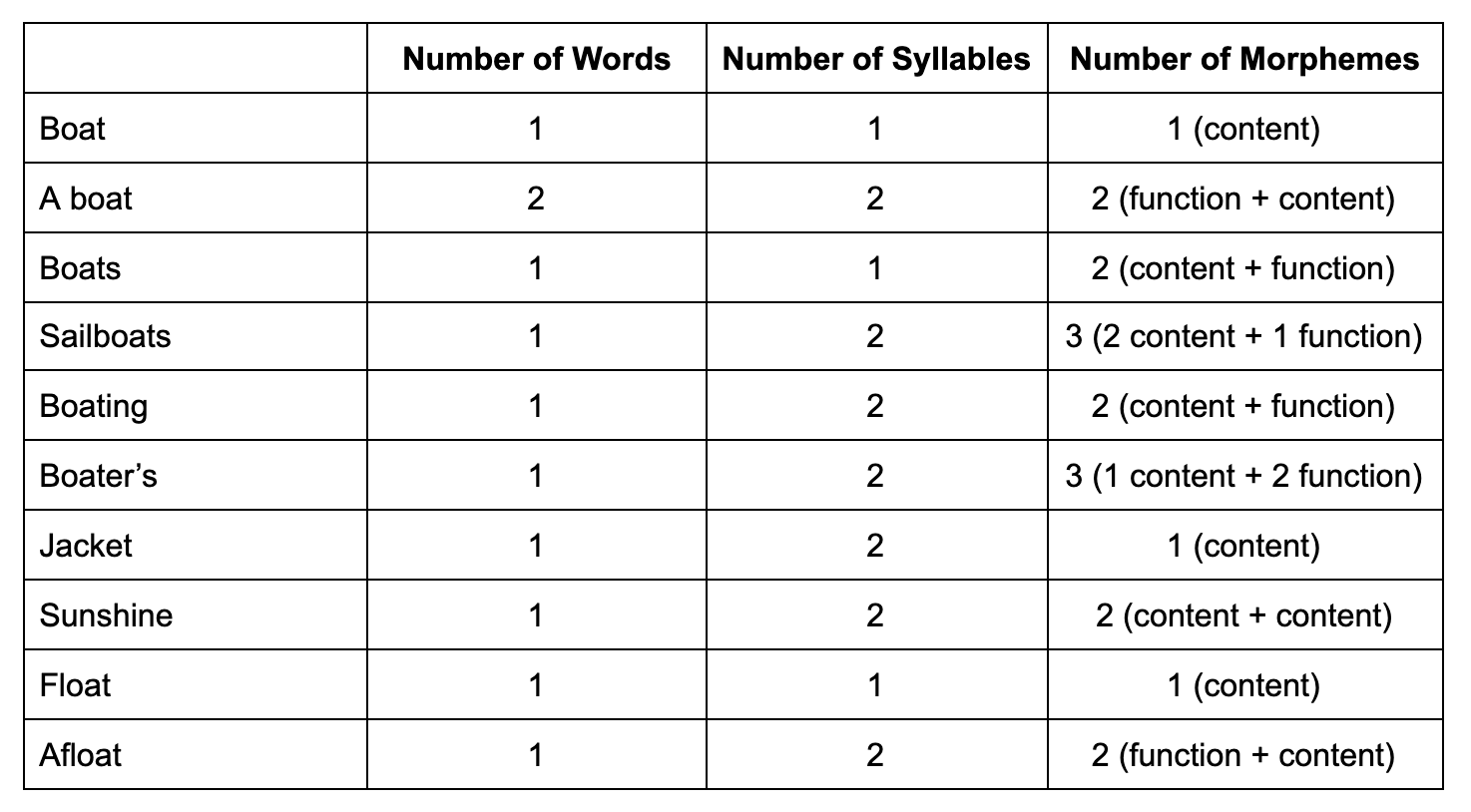

See the chart below to understand how words, syllables, and morphemes function independently of one another.

Grammatical Morphemes Occurring Early in Development

Thanks to Roger Brown, who in 1973 developed a framework called “Brown’s Stages,” we now have research-based expectations of a typical child’s development of morphemes. In the field of speech and language therapy, this framework helps therapists determine whether or not a child has delays. It also helps them choose appropriate goals to target.

According to Brown’s Stages, a child will begin to use grammatical morphemes around 27-30 months. The earliest-developing grammatical morphemes tend to be the present progressive “-ing” (e.g., “reading,” “running,” etc.), prepositions “in” and “on,” and regular plural “-s” (e.g., “cars,” “flowers,” etc.).

In the next stage, at 31-34 months, a typical child starts using irregular past tense (e.g., “went,” “fell,” etc.). They’ll also start using possessive “-s” (e.g., “Mommy’s”) and the verb “to be” (in its whole form) when there’s no other verb in a sentence (e.g., “it is”).

At 35-40 months, we expect a child to begin using articles (e.g., “a,” “the,” etc.). We start hearing regular past tense “-ed” (e.g., “chewed”) and the third person regular tense “-s” (e.g., “jumps”).

Last, at 41-46+ months, a child will begin using more complex grammatical morphemes, such as third person irregular forms (e.g., “has”) and more.

What’s an MLU?

“MLU” is an acronym for Mean Length of Utterance. In this case, “Mean” refers to an average, and “Utterance” refers to a phrase or a sentence. Therefore, when we say “MLU,” we are talking about the average number of morphemes –– not words –– in a child’s phrase or sentence.

An MLU attempts to quantify a child’s expressive language skills. More specifically, it can give therapists another data point morphological and syntactic (phrase and sentence structure) skills.

Calculating MLU

Step One: To determine a child’s MLU, start by taking a language sample. Simply write down everything your child says spontaneously. It’s important to gather enough utterances so that the MLU you calculate is representative. Normally we suggest a minimum of 50 spontaneous utterances.

Example:

the fox jumped over the logs and now it swims swim fast fox the water’s so cold he’s unhappy

Step Two: Next, break down the language sample. List each phrase or sentence, one by one, and determine the number of morphemes within each.

Example:

The fox jumped over the logs. (8 morphemes)

And now it swims. (5 morphemes)

Swim fast, fox! (3 morphemes)

The water’s so cold. (5 morphemes)

He’s unhappy. (4 morphemes)

Step Three: Add up the number morphemes from the entire language sample. Then, divide that by the number of utterances in your sample.

Example:

8 + 5 + 3 + 5 + 4 = 25 morphemes

25 morphemes / 5 utterances = 5

In the above example, the MLU is 5.0. Remember, however, that you’ll need a minimum of 50 utterances to generate a valid MLU for your little one.

MLU Norms

Thanks again to Roger Brown, we know what to expect of a typically developing child with regard to their utterance length at different ages:

12-26 months: average MLU is 1.75 morphemes, with a range from 1.0 to 2.0

27-30 months: average MLU is 2.25, with a range from 2.0 to 2.5

31-34 months: average MLU is 2.75, with a range from 2.5 to 3.00

35-40 months: average MLU is 3.5, with a range from 3.0 to 3.75

41-46+ months: average MLU is 4.0, with a range from 3.75 to 4.5 (2)

How to Teach Morphemes

Remember how every tiny unit of language with meaning is a morpheme? This means that you’re literally using morphemes any time you talk to your child. A typically-developing child will learn morphemes just by listening and practicing.

However, if your child is struggling to pick up morphemes and needs some extra help, try these ideas.

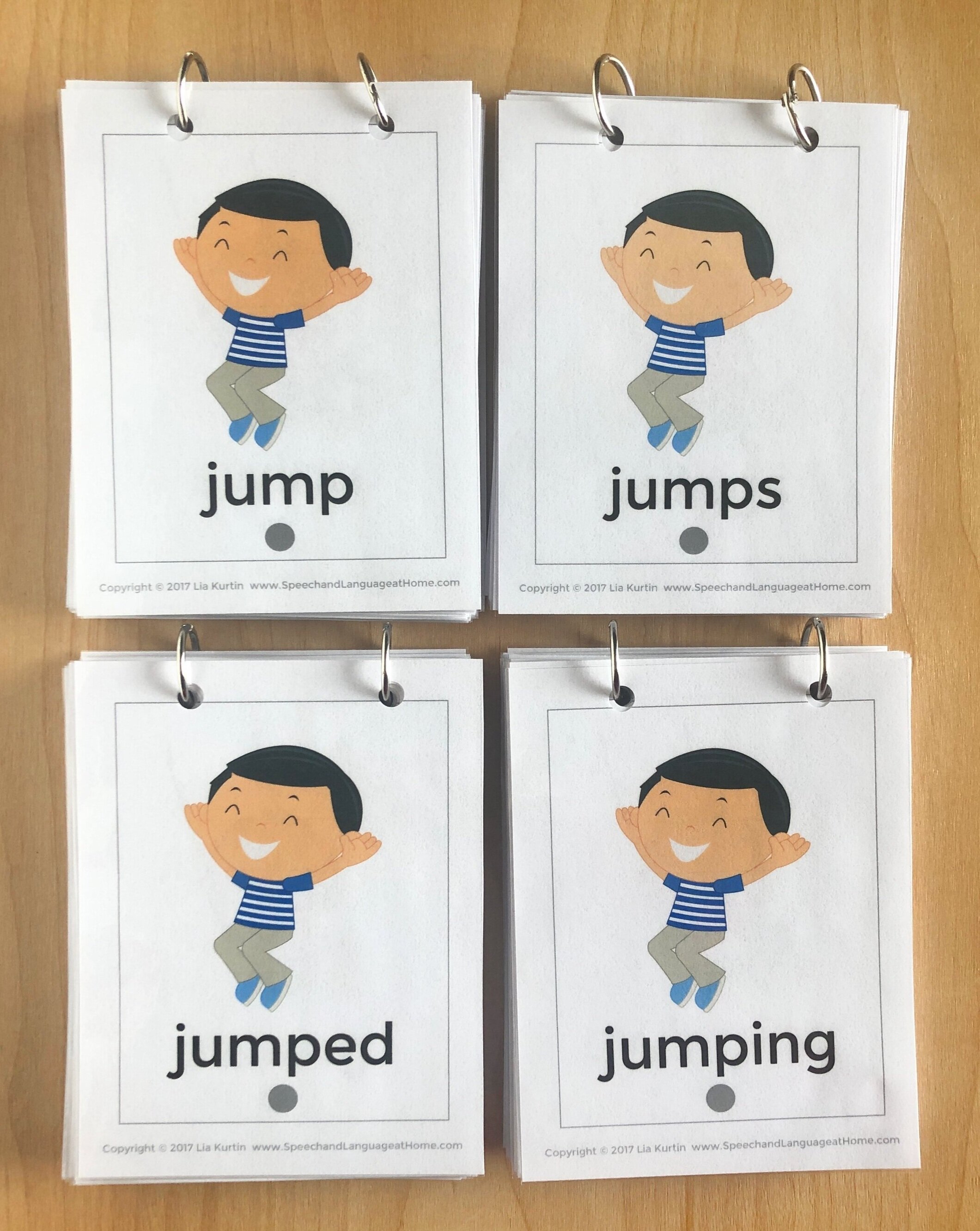

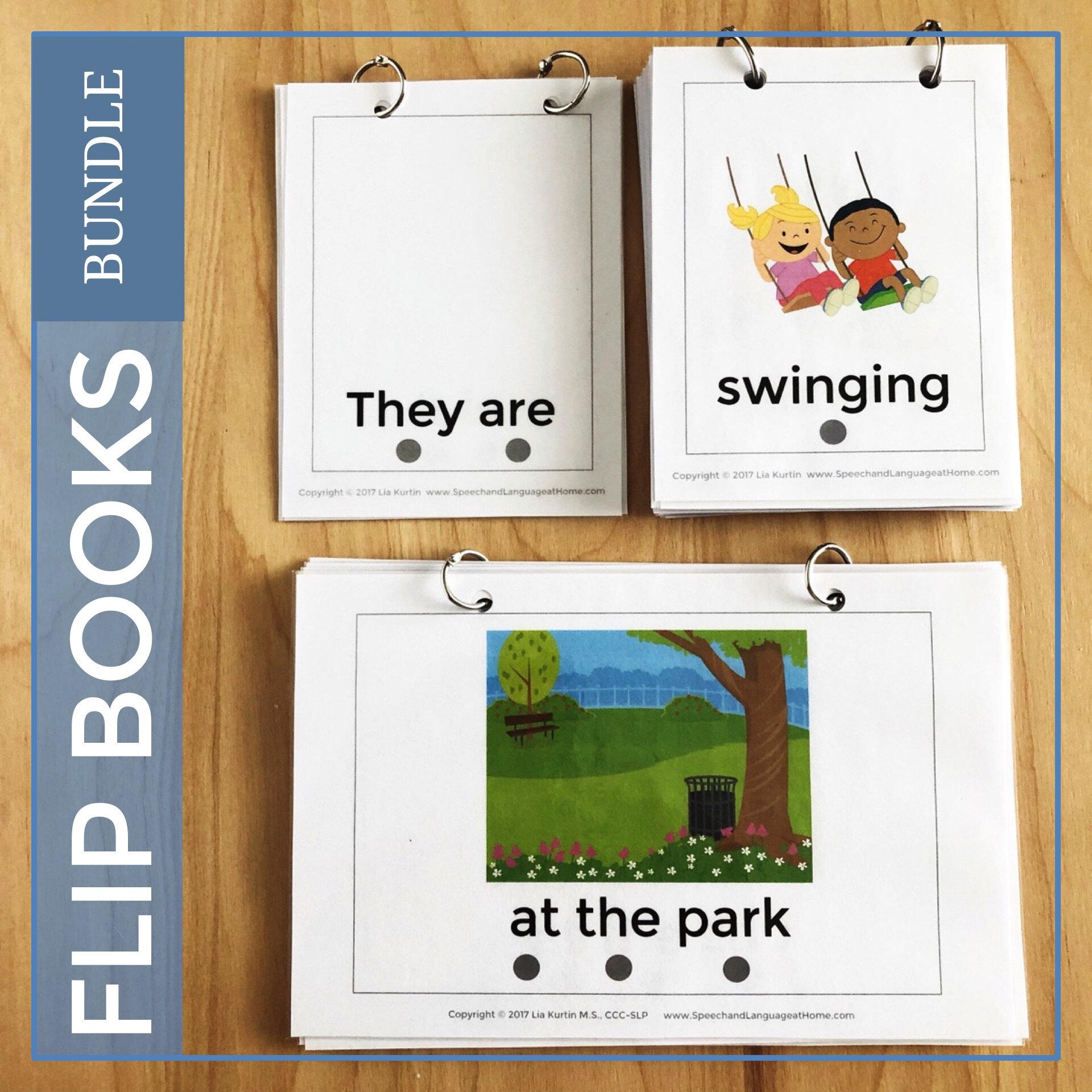

Flip Books

Target morphemes and increase MLU with flip books! I love these books because they provide a structured, explicit teaching activity for morphemes, grammar, and sentence structure. Consider what your child needs to practice, and then grab the respective flip book. Choose from our Adjective and Preposition Flip Books, our Verb Tense Flip Books, or our Noun and Pronoun Flip Books. If you need them all, grab this discounted bundle.

Focused Stimulation

Another way to teach morphemes is through a strategy we’ve talked about before called focused stimulation. Pick a fun, play-based activity with your child and choose a morpheme to target. Next, try to use the morpheme frequently as you do the activity together. For example, if you’re targeting the plural “-s” while playing with a barn, label all the animals (e.g., “cows,” “lots of ducks,” “I see chickens,” “only one rooster,” etc.). See if your child starts using the plural “-s,” too!

Sources

Brown, R. (1973). A first language: The early stages. London: George Allen & Unwin.

“Brown’s Stages of Syntactic and Morphological Development”